We have previously described the role of surfaces in fouling. In this third article, we will elucidate the role of fluid flows and explain why unexpected behaviors arise from the interactions between fluid flow and foulants.

By Isaac Appelquist Løge and Benaiah U. Anabaraonye

![Figure 1: Fouling on a threaded surface [1]. The threaded surface allows us to investigate the distribution of flow forces on a surface and how they affect deposition distribution. (a) The simulated flow forces are shown; (b) Experimental results of deposition on a threaded surface.](https://b1982122.smushcdn.com/1982122/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2023/10/figure-1-2.jpg?lossy=1&strip=1&webp=1)

In this article, we present insights on why the effect of flow cannot be easily predicted. We conclude by demonstrating the practical applications of fluid flow for fouling mitigation.

A third deposition regime

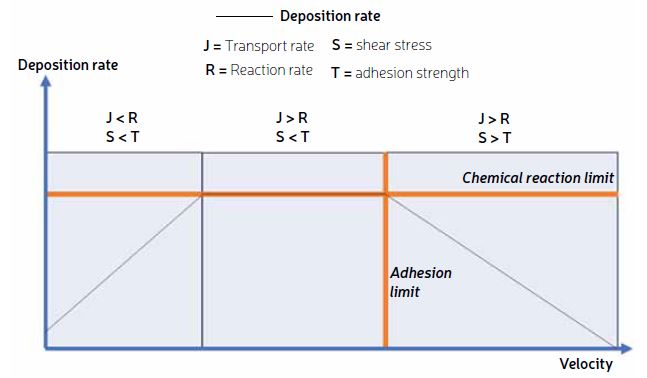

Two main deposition regimes as a function of fluid flow rate are generally considered in the literature. Firstly, a reaction-limited regime, where the rate of transport of foulants to the surface is faster than the reaction rate at the surface. Secondly, the transport-limited regime, which exists at higher flow rates, where the surface reaction rate is faster than the rate of transport. In a recent study, we illustrated deposition behavior at a transport-limited regime[¹].

We simulated the flow forces distributed across a threaded surface and measured the distribution of the foulant using X-ray CT (Figure 1). We used a threaded surface to create a large variation in the flow forces. We observe that areas of high flow velocities had the most surface deposition. In contrast, a previous study conducted in a stirred reactor found that the least amount of deposition occurred at areas of high flow rates [²].

We propose a third regime, adhesion-limited regime, to explain why higher flow rates can yield lower fouling rates. In this regime, detachment processes are accelerated by higher flow rates because the flow forces are larger than the adhesion strength of the particle. The three deposition regimes are summarized in Figure 2.

The conditions under which fouling is formed

The interactions between flow forces and foulants determine whether foulants will either stay adhered to the surface or detach from it. The resilience of a foulant is determined by its adhesion strength and ability to withstand external forces, both properties are determined by the conditions under which it was formed. For example, we have shown that both fluid flow rates and concentrations greatly influence fouling resilience. At lower flow rates, we observed isolated crystals on the surface, which in turn have a lower resilience [¹].

We have also shown that at sufficiently high concentrations, foulants exhibit a complex shape structure that is more susceptible to detachment forces (Figure 3) [³]. Similarly,. a group of researchers observed an interesting behavior in FeCO₃. They showed that when FeCO₃ is formed at below 60°C, they more readily detach from surfaces. We therefore recommend that while predicting the fate of foulants on a surface, it is important to consider the conditions under which they were formed.

Utilizing flow forces as mitigation strategy

Flow forces are being used as an online mitigation strategy for fouling in heat exchangers. There is a lot of research on how to utilize flow forces. Two main strategies exist: either changing what or how the fluid is injected or increasing the degree of turbulence in the flow.

For example, injecting projectiles with the fluid has been shown to effectively mitigate fouling. A group of researchers showed that sponge ball projectiles with a diameter of 20 mm, not only limit the formation rate of fouling but also limit how thick the deposits become [⁵].

However, they observed that the injection of particles had little effect when the surface was already fully covered. Therefore, using particles might be useful to abate fouling in the early stages of its build-up, when the foulant has a weak adhesion to the surface. It could also be enough to change how fluids flow. Turbulence could be achieved by installing constrictions in the flow field. Crittenden et al. [⁷] installed wires that increased turbulence and observed that fouling was mitigated. Such modifications can reduce fouling by 85%, with likely reasons such

as higher shear stress, oscillatory flow mixing, and vortices arising from the constricted geometry. While an 85% reduction in fouling is impressive, it CaSO₄, which is considered a “soft” foulant. It was not tested for strongly adhering foulants.

![» Figure 3: Fouling behavior as a function of (a) flow and (b) concentration. (a) At low flow rates, isolated crystals are formed and these are more susceptible to detachment forces [1]. (b) At low concentrations, deposits are formed with a large attachment area and a high resilience towards detachment. At high concentrations, foulants are more susceptible to detachment.](https://b1982122.smushcdn.com/1982122/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2023/10/figure-3-2.jpg?lossy=1&strip=1&webp=1)

Conclusion

Currently, the predictive models for fouling build-up do not consider the interaction between fluid forces and foulant resilience adequately. This results in wrong predictions, which could be costly when designing, building, and operating heat exchangers. Understanding the effect of flow on fouling will enable engineers to better design heat exchangers and implement more effective mitigation strategies.

Author Announcement

Isaac Appelquist løge has been selected as a finalist for the IChemE global awards (young researcher) in recognition of his work on crystallization fouling. Isaac is grateful to the Danish Offshore Technology Centre for funding his doctoral studies research. We at Heat Exchanger World wish Isaac good luck in the final which will be held in Birmingham, UK, on the 30th of November 2023.

About the authors

Benaiah U. Anabaraonye is a research scientist and program manager at the danish offshore technology Centre. He has a PhD in Chemical Engineering from Imperial College london.

Benaiah U. Anabaraonye is a research scientist and program manager at the danish offshore technology Centre. He has a PhD in Chemical Engineering from Imperial College london.

Isaac Appelquist Løge completed a PhD on crystallisation fouling, using novel methods to visualise fouling formation. He is currently researching what makes fouling detach and what makes it stick.

Isaac Appelquist Løge completed a PhD on crystallisation fouling, using novel methods to visualise fouling formation. He is currently researching what makes fouling detach and what makes it stick.

Isaac Appelquist løge and Benaiah U. Anabaraonye will be publishing regular articles as part of their Research Series across multiple issues of Heat Exchanger World. All articles will be available in our online archive: https://heat-exchanger-world.com/category/technical-articles/.

References

- Løge, I.A. et al. (2022) ‘Scale attachment and detachment: The role of Hydrodynamics and surface morphology’, Chemical Engineering Journal, 430, p. 132583. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.132583.

- Davoody, M. et al. (2019) ‘Mitigation of scale formation in unbaffled stirred tanks-experimental assessment and quantification’, Chemical Engineering Research and Design, 146, pp. 11–21. doi:10.1016/j.cherd.2019.03.032.

- Løge, I.A. et al. (2023) ‘Crystal nucleation and growth: supersaturation and crystal resilience determine stickability’, Crystal Growth & Design, 23(4), pp. 2619–2627. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.2c01459.

- Farida, W. et al. (2012), ‘Effect of precorrosion and temperature on the Formation rate of iron carbonate Film’, 7th Pipeline technology conference

- Malayeri, M.R. and Jalalirad, M.R. (2014) ‘Mitigation of crystallization fouling in a single heated tube using projectiles of different sizes and hardness’, Heat Transfer Engineering, 35 (16–17), pp. 1418–1426. doi:10.1080/01457632.2014.889448.

- Subramani, A. et al. (2012) ‘Vibratory shear enhanced process (VSEP) for treating brackish water reverse osmosis concentrate with high silica content’, Desalination, 291, pp. 15–22. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2012.01.020.

- Crittenden, B.D. et al. (2014) ‘Crystallization fouling with enhanced heat transfer surfaces’, Heat Transfer Engineering, 36(7–8), pp. 741–749. doi:10.1080/01457632.2015.954960.